Introducing: In our ‘Field Notes’ series, members of the Menaqua Foundation team write about their visits to and experiences in our project countries. In this edition, Sammy Kayed, local agent for Menaqua in Lebanon, reports from Arsal, an agro planting site in the upper North of Lebanon.

“It’s easy to blame the homogenizing force of the dominant global economy and go on with your day”.

We tend – understandably – to place an extremely high value on knowledge that is produced scientifically and is technical in nature. After all, this knowledge can be measured, proven, repeated and applied in standardized and compartmentalized ways. It’s attractive for its commercial value and has brought about some of our most impressive advancements.

But as we exponentially produce and assign value to this kind of knowledge, there is a mass extinction underway in the diversity of cultural and place-based knowledg e that connects us to land, ecosystems, seas and each other. One has to wonder whether it is a coincidence that as the diversity of knowledge from places and cultures disappears, biological diversity is also collapsing. It’s easy to blame the homogenizing force of the dominant global economy and go on with your day. But it’s also important to understand the relationships between different knowledge and biological expressions as a portal to preserving what’s left.

e that connects us to land, ecosystems, seas and each other. One has to wonder whether it is a coincidence that as the diversity of knowledge from places and cultures disappears, biological diversity is also collapsing. It’s easy to blame the homogenizing force of the dominant global economy and go on with your day. But it’s also important to understand the relationships between different knowledge and biological expressions as a portal to preserving what’s left.

Stewards of biological diversity

Numerous reports have been published recently recognizing that indigenous people who are attached to their ancestral lands are some of the best stewards of biological diversity. As these links are being established, the question we must keep asking is: how can we gain the best of both worlds, and more meaningfully bring technical knowledge holders and indigenous knowledge holders together?

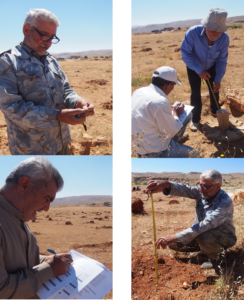

We began answering that question during the implementation of a pilot project in Lebanon. In Arsal, the north-eastern area of Lebanon, we worked with a group of smallholder farmers (see here for an interview with their senior farmer Mr. Mahmoud) to plant native fruiting forest trees using Cocoon technology. We followed the technical specifications of Land Life Company, which developed the technology. These were the type of soil to plant in, the slope restrictions, climate limitations, the removal of rocks, the procedure for correctly situating the tree in the Cocoon and, most interestingly, the depth that the Cocoon should be placed – 50 cm below the surface of the ground.

Participatory planting

Even though the technical aspects were straightforward, we decided to carry out the pilot in a participatory fashion and attempt to give equal value to the farmers’ experiential and place-based knowledge. After all, they have been working these fields for many generations and were excited about the prospects of the Cocoon technology and what it can deliver, namely:

- improved survival rates of newly planted trees

- an expanded planting season

- water savings

But the farmers’ years of experience in that soil and under those weather conditions prompted them to question the depth at which the Cocoon should be placed. They explained to the technical experts that the deeper soils are an effective and necessary temperature regulator. As a result, planting at depth could keep the water in the Cocoon’s reservoir from freezing when temperatures dip below zero.

Levelling the knowledge playing field

We agreed together that the farmers would plant a handful of the Cocoons slightly deeper than the others and self-monitor the performance of this scenario. Sure enough, in a humbling turn of events, the tree survival rate of those deeper Cocoons was better than the ones that followed the exact technical procedure. This not only improved the tree survival rate, it also improved the relationship between the technical experts involved and the farmers by levelling the knowledge playing field and reversing the norms of who gets to teach whom.

This small example of the power of valuing indigenous knowledge is yet another reason why we need to improve our ability to listen and step down from our entitled positions as holders of the ‘right’ or ‘superior’ knowledge as we try to make the world a better and more localized place.